Mouthwashing Review | RPGFan

In space, no one can hear you gargle.

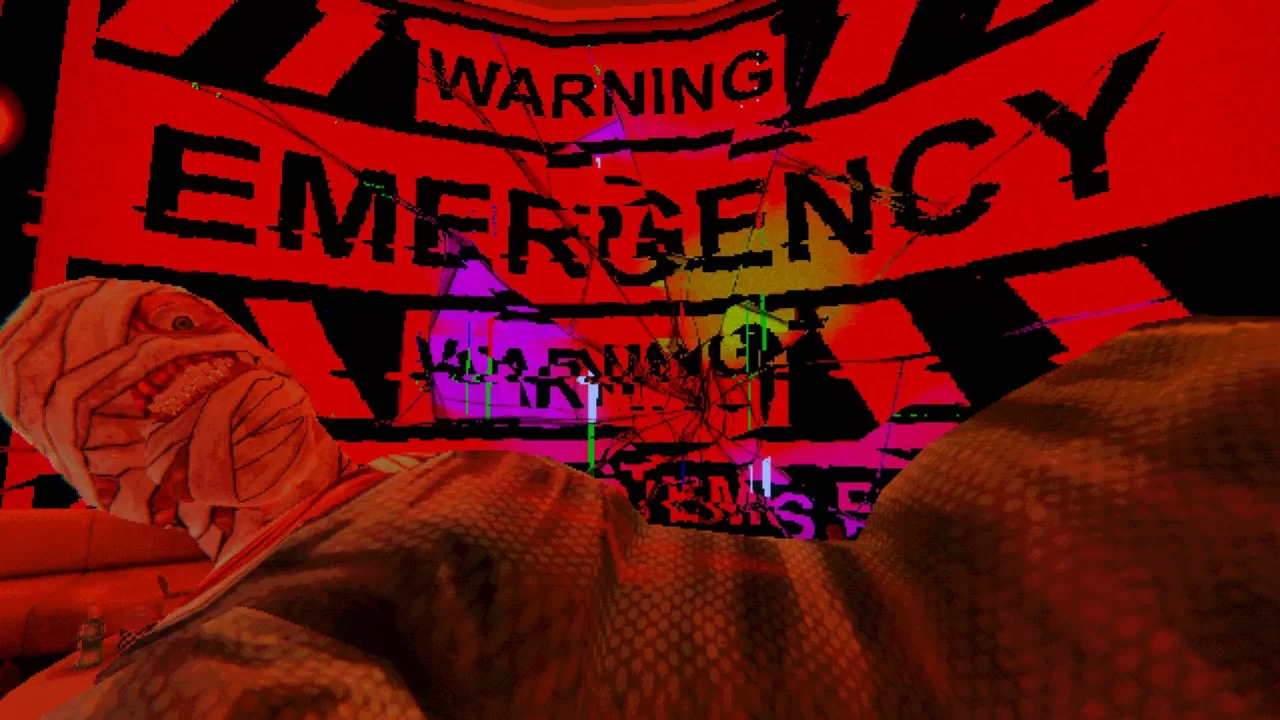

Mouthwashing sees you as a spaceship captain aboard an interstellar freighter on its long journey home. The ship’s computer warns that a minor course correction is needed to avoid an asteroid. But for reasons unknown, you decide to steer into the asteroid instead.

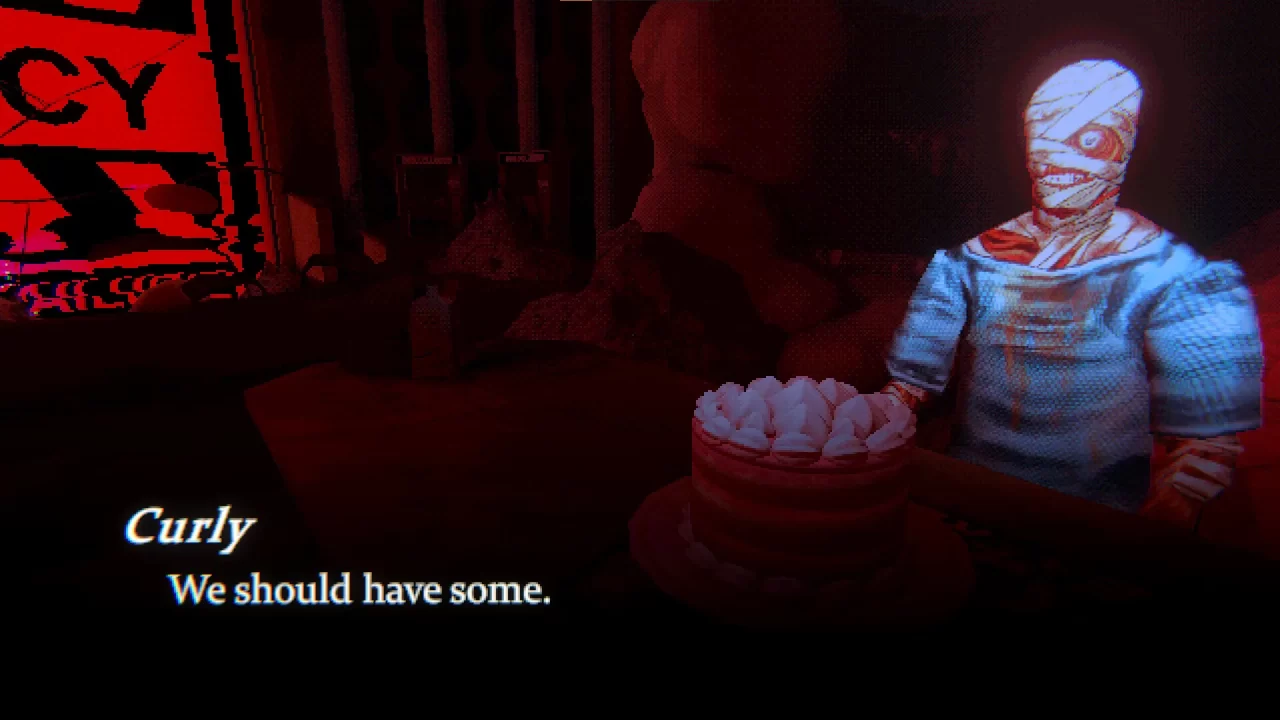

Our small crew of five actually survive the ensuing crash, but with limited food rations, their only hope is a massive supply of — wait for it — mouthwash to sustain them until rescued. Also, the ship’s captain, Curly, was horrifically maimed in the incident and is now stuck in the medical bay, lacking limbs and the ability to speak (outside of crying in pain). He also needs to be fed a constant supply of painkillers lest his injuries catch up with him. Our cast might have the freshest breaths in the galaxy, but their ability to cope with their harrowing circumstances becomes increasingly grim as they deal with steadily depleting supplies and the mental toll of uncertain survival.

First, I recommend playing this game blind. Mouthwashing was an instant hit and has quickly found a dedicated fanbase thanks to its memorable cast and story. It’s also very short: The 2- to 4-hour length and on-rails nature make it a great “movie-esque” experience (even priced about the same as a ticket). To mix and match a few games: Mouthwashing hits the same disturbing depths of a Silent Hill game, visually reminds me of FromSoftware’s PS1 adventure-horror game Echo Night, has that deliberate horror-game-meets-horror-movie influence of Until Dawn, and has the short and sweet scope of What Remains of Edith Finch. And all of these games feature many people dying. So, uh: Vibes check!

Mouthwashing is developer Wrong Organ’s second title after How Fish is Made, a philosophical sojourn into the ups and downs of life as a sardine. It’s a strange little game that leaves itself open to interpretation. There’s also a DLC chapter where you play as a small Eldritch mass that rolls around (Katamari-style) and meets the Mouthwashing cast! Although it’s not required playing ahead of Mouthwashing (though it is freeware), it demonstrates Wrong Organ’s ability for crafting clever and tight narratives — where even short amounts of time with a person (or fish) can reveal a lot about them — especially if they’re under pressure.

Even during our brief stay aboard the freighter, there’s so much to say about each of the five main characters. It’s their desires, their struggles, their fears — and especially the contradictions — that make them interesting. Is it bad that our ship’s nurse Anya gets squeamish around the severely injured Curly? Or is it bad if our mechanic Swansea pours 15 years of sobriety down the drain to survive off high-alcohol mouthwash? What could go wrong? (In a word: everything.)

Meanwhile, it’s been ages since I’ve been so upset with a game’s villain, a person both truly twisted and unforgivable once the truth comes out. And while our main baddie is the worst of the bunch, the rest of the crew isn’t entirely off the hook for their choices either. But the reveal is subtle, and it pulls the curtain back on the entire game’s narrative, even giving new context to earlier parts in the story that makes Mouthwashing worth replaying (if you can stomach it).

Indeed, a major strength of Mouthwashing is that character conundrums are worth ruminating on and don’t feel forced or arbitrary — a genuine sense of history builds its confrontations. But otherwise, their personalities are easy to parse and come from sensible places (and dialogue is even colour-coded for convenience, like Anya figuratively and literally being the “blue” one). Meanwhile, character mental states are thoroughly divulged and sometimes literally explored through bizarre dream sequences. This speaks to Mouthwashing’s final half where it goes full space-horror and that delirium and darkness take hold of the story.

Gameplay largely occurs through linear sections aboard the freighter; however, the story is told out of order. You take control of a pre-crash Captain Curly, with co-pilot Jimmy picking things up during post-crash sequences, alternating between the two protagonists to piece everything together. Tasks take the form of minor puzzle-solving and straightforward point-and-click mechanics. There are about three “hands-on” segments to keep you on your toes, but there are no health bars or Game Overs to concern yourself with. Mouthwashing is definitely a story-game, not a gamey-game. As a fan of puzzles, it left me a little wanting, as these are easily the least interesting parts of Mouthwashing. But for those just wanting to get to the “juicy bits” (of which there are many), it’s serviceable and no part will leave you stuck for too long. I still recommend walking around the ship to chat with the crew and take in the environmental storytelling of Mouthwashing’s time-hopping narrative (such as the board game in the ship’s lounge changing each chapter).

Music-wise, Mouthwashing flips between starry lo-fi ambiance, complete silence, and creepy electronic tunes designed to put you on edge. It’s all very immersive and delivers contrasting sounds very well. The game has very little voice acting (outside of a few screams and one animatronic corporate mascot, Polle), so it’s nice to hear so many unique pieces of music made specifically for the one scene in which each appears.

I also enjoy the cheeky radio “muzak” and a mixed-media TV set that plays live-action clips and old-timey cartoons. It all gives a false sense of security, comfort, and foreshadowing in a game otherwise teeming with doom and gloom. And again, without voice acting, the game does well relying on sounds. White noise, loud alarms, footsteps clanging through long, empty metal halls — and it’s hard to forget Curly’s painful cries throughout the ship! It all clawed at the back of my brain, even when no immediate threat presented itself.

And on that note, it’s worth talking about Mouthwashing’s horror as I am the ideal horror audience. That is to say, I’m bad with it, and I get creeped out easily! But I appreciate how the game doesn’t use many cheap scare tactics for its chills or thrills. To be clear: A LOT of bad things happen. The worst of the worst, in fact. And it’s all very gruesome… but it also looks like a PS1 game — so on the “bright side” no fleshy parts look too gooey, textured, or realistic. Yet a lot of the violence packs a punch, even when it’s off-screen, simply due to their effective setups. I viscerally felt the horror through difficult scenarios that’ll make your skin crawl. A few scenes had me going (direct quote): “Noooo—” or just left me with my mouth wide open, but it was never anything I needed to look away from. There’s a fair amount of pitch-black hallways, flickering lights, blood splatters, and a concerning amount of empty mouthwash bottles that effectively relay the fear and misery. Still, you won’t suddenly be chased by something out of the darkness, at least not without ample sensory warning (one surprise encounter ends up being more cheeky than actually distressing). This is all to say that Mouthwashing carefully crafts how it scares people.

On the downside, character animations are simple and repetitive, and the models seldom emote (with their admittedly great dialogue doing most of the heavy lifting). I find it strange that Anya has cartoonishly huge eyes, and that Swansea’s arms look haphazardly attached. And characters rarely walk so much as they just appear in place. It can feel a little low budget, but it’s quite impressive how Wrong Organ can work within its limits, relying on a good story, cast, and various moods to pick up the slack.

Worth mentioning is the use of transition shots taking a “glitched” effect (a gamer-targeted horror if there was one), and the game often cuts to parts of the story when they hit a dead-end or to quickly bridge storytelling gaps. It’s genuinely great when the game transitions into an emergency situation without any context given! Additionally, semi-random text pop-ups (often compared to Neon Genesis Evangelion title cards) relay thematic messages and warnings like a subliminal shot to the head.

It would be easy to write off Mouthwashing for its short runtime or linear nature, but the experience is very well-paced, with no scene feeling superfluous or running too long. Like any good horror movie, you’re slowly eased into the madness before sliding down it uncontrollably. A few light moments offer needed variety, and periods before the crash tend to feel “safer” than those after the crash — but it’s always building towards heavier themes and climaxes. I believe a few scenes could have benefited from further elaboration, as some story beats aren’t always crystal clear, but this could just be me wanting to spend more time with everyone.

While the theme of “taking responsibility” is plastered all over the game, I became more fascinated about what Mouthwashing has to say about disability and mental health. Despite Captain Curly taking the lead in all the “before crash” segments, it’s interesting that his role diminishes to an injured bystander during the “after crash” chapters. Most of the main cast is clearly going through serious problems, often rooted in circumstances beyond anyone’s control. Yet, these burdens we try to fight or hide can resurface in awful ways, especially when they clash against others similarly facing their own demons. Maybe if we could better address our problems at their source, we could avoid worse problems later on. But it’s never really that simple, is it?

While a sorrowful game like What Remains of Edith Finch chooses to end on more of a “life is short, but beautiful” angle, the opposite can be said here: Mouthwashing waits until the last minute to deliver its final, devastating punchline. Even if the gameplay here isn’t revolutionary, it’s hard not to be drawn by the gravity of games that “go big on story” (like how Yoko Taro games tend to revel in delightfully twisted storytelling). After a certain point, you simply can’t look back and need to see how this ends, even if it’s all in tears. But the best parts of Mouthwashing have sat in my mind for a while now, and Wrong Organ has quickly established itself as a developer worth keeping a creepy, unblinking eye on.