Pentiment Review | RPGFan

Pentiment is coated, like a canvas under layers of paint, with astute depictions and examinations of 16th-century history, religion, art, literature, class, and gender roles within the Holy Roman Empire. It’s also a murder-mystery adventure game that opts for character role-playing over puzzles and robust conversations over deduction. Playing through it often felt like reading a well-researched book, exacerbating its functional weaknesses as a game, yet emphasizing its inability to tell its incredible interactive narrative in anything but game form. Since I started it and long since finishing it, Pentiment clouds my thoughts and demands that I tell others about it, even though I know its appeal is limited.

Obsidian Entertainment are best known for their quick and creative sequels to the big-franchise RPGs of landmark studios like BioWare and Bethesda—Star Wars Knights of the Old Republic II, Neverwinter Nights 2, and Fallout: New Vegas come to mind. While they may have long existed in the shadows of giants, Obsidian have undoubtedly proven their ability to write complex stories rife with entertaining dialogue and freedom of choice for players. Pentiment, originally released on Windows and Xbox platforms in 2022 and for PlayStation 4, 5, and Switch in 2024, is Obsidian scaling down the physical world and mechanics to their bare necessities while plumbing the depth of their dialogue systems.

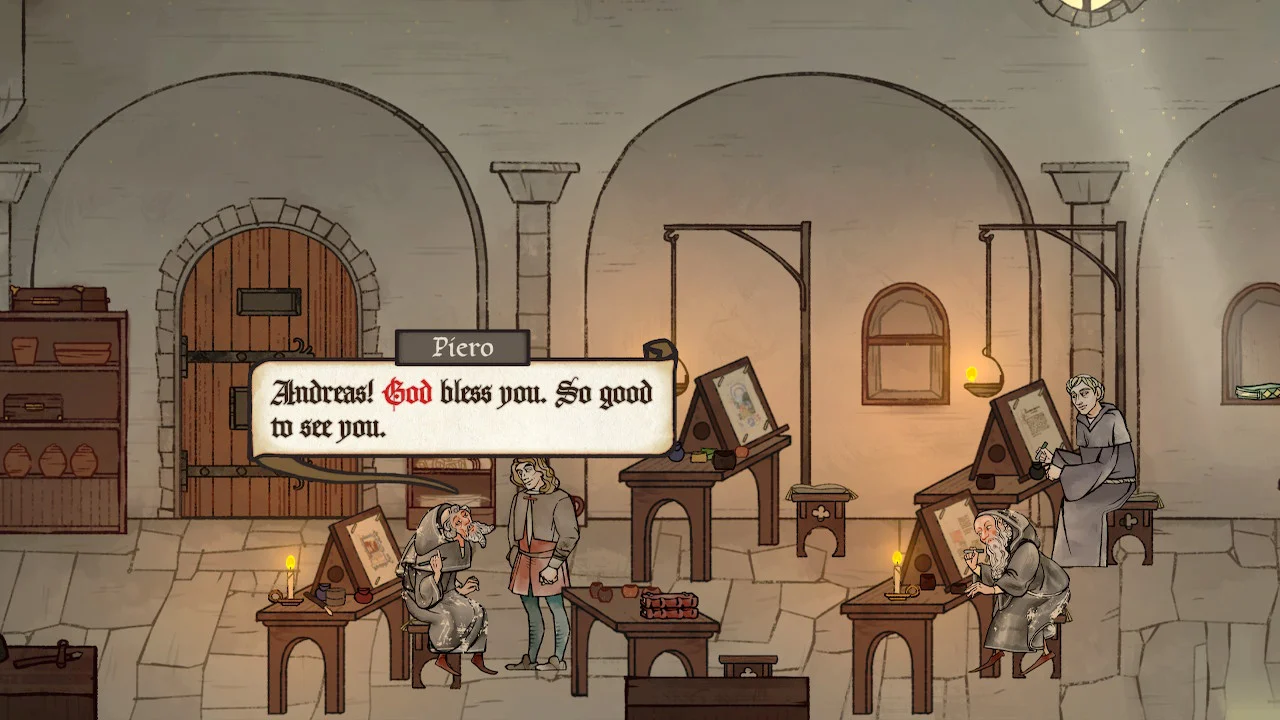

Players primarily control Andreas Maler, a journeyman artist honing his craft in the Benedictine monastery of Kiersau Abbey, overlooking the small Bavarian town of Tassing. Now crowned by Catholicism, Tassing still bears ruins and remnants of the prior Romans and the pagans before them. Andreas works in the abbey’s scriptorium, where he aids in the even-antiquated-for-1518 practice of penning and illustrating commissioned books by hand. The 1500s backdrop means that major historical events like the Protestant Reformation and the German Peasants’ War are going on, and traces of them show through.

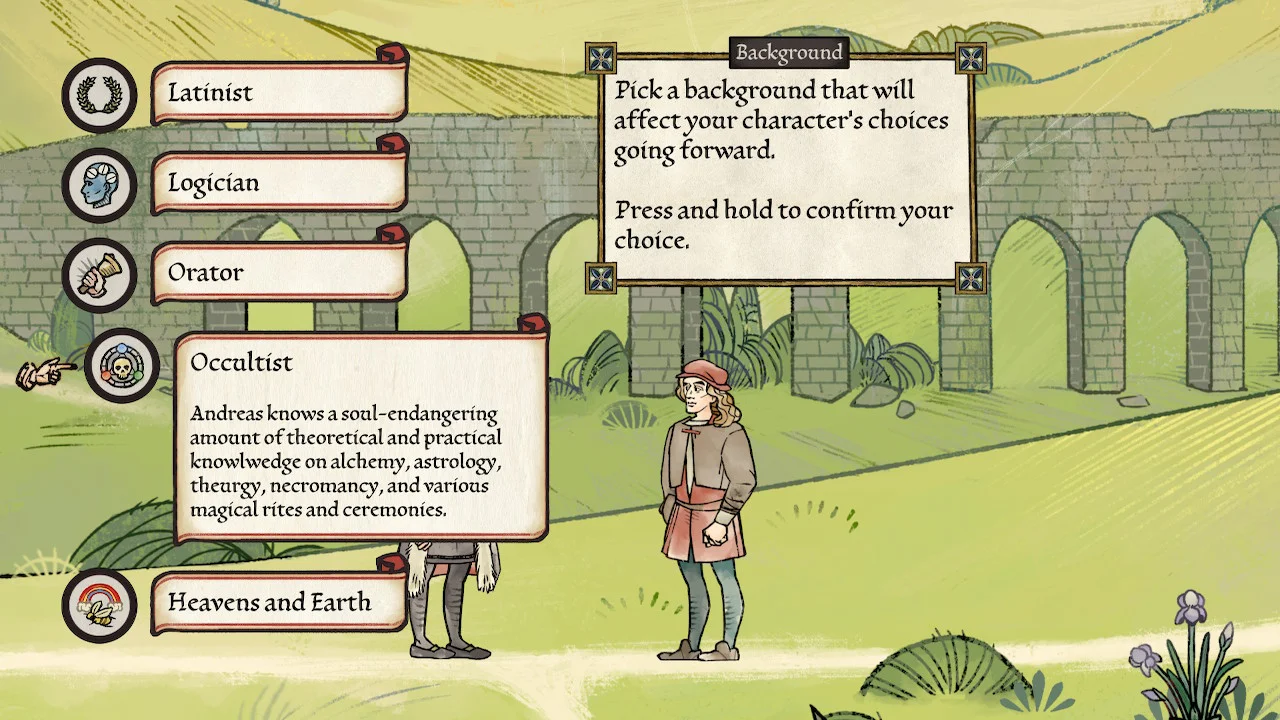

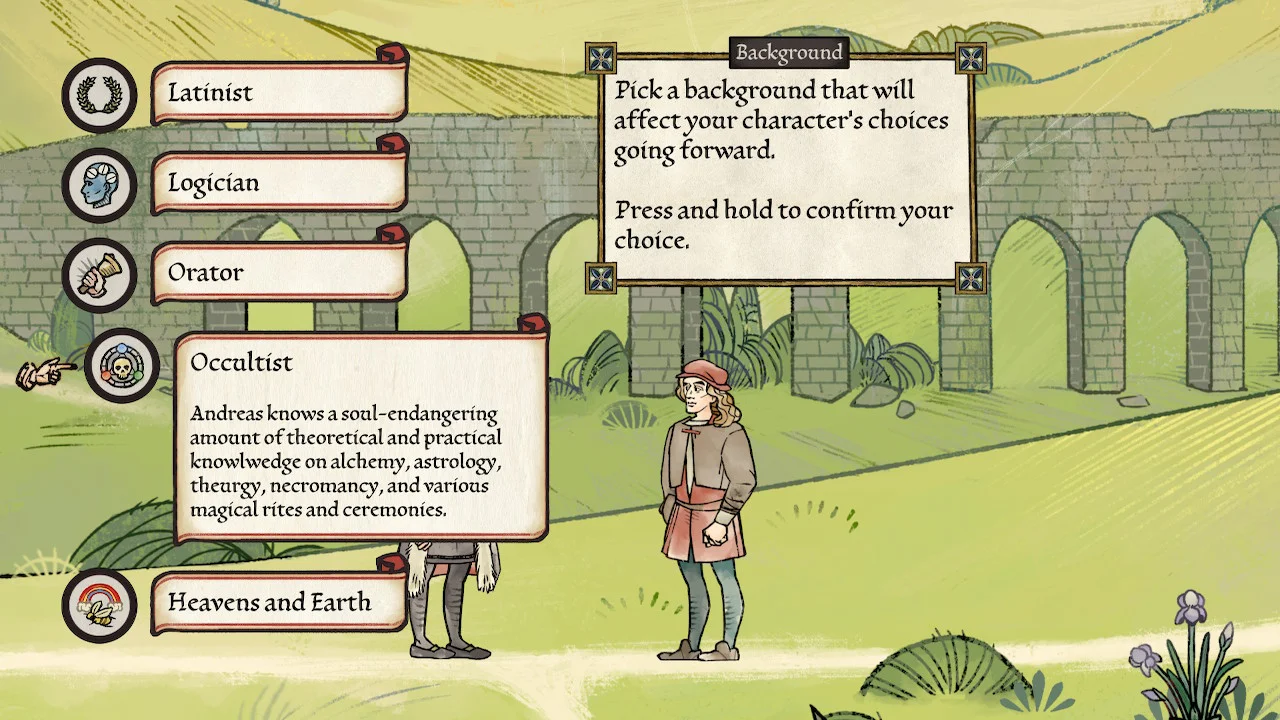

When a murder rocks the abbey, it’s the outsider Andreas who decides to freely roam about the town and abbey in a small, semi-open world of horizontal vistas, devoting chunks of each day a la the Persona series to various actions and leads. If you dine with the stone mason’s family, you might learn why he was arguing with the murder victim the previous day. If you help the elderly peasant clean her house, she may warm up enough to tell you of Tassing’s pagan roots and dark undercurrents. Through dialogue choices and a series of selectable character skills early in the game, players can form Andreas’ past just as fluidly as they plot his and the town of Tassing’s future.

My Andreas had schooling in Italy, including studies in theology and under-the-table occultism. He also belonged to the “Hedonist” class, meaning that he’d occasionally flirt with the nuns or villagers and had experience with the crasser sides of life. Moreso than perhaps any game I’ve ever played, Pentiment continually lets you dictate your past throughout its roughly fifteen-hour runtime, allowing me to flesh out my Andreas in ways that were surprising even to me. In this way, Obsidian adhere to their RPG roots.

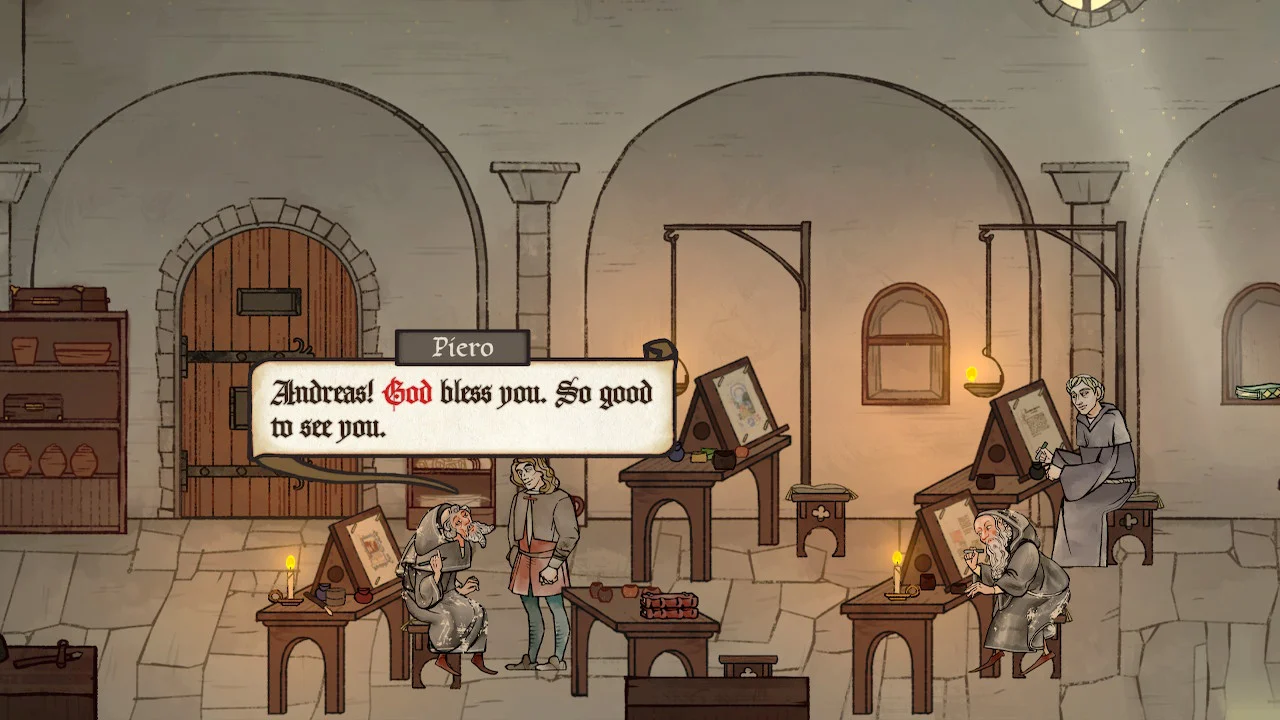

One of Pentiment’s more notable draws is its art style. Andreas fluidly moves about on a colorful 2D plane that looks like a painting lifted from medieval manuscripts. Elderly characters are depicted with an older style and fading lines. Brother Sebhat, an Ethiopian monk visiting the abbey, is drawn in a style entirely separate from the main European cast. It’s colorful and striking, if not exactly always beautiful. There are moments where the creative potential of the art style is unbridled, such as when Andreas retreats into his dream world to consult his council of consciences including historical, literary, and legendary figures like Socrates, Beatrice (presumably of The Divine Comedy), the mythical Christian king Prester John, and Grobian, the patron saint of vulgarity. Occasionally, Andreas dreams of sailing to this illusory council to recap major decisions and their stakes.

Players can also occasionally hear out the dream council amidst tricky dialogue situations, similar to the way the protagonist of Disco Elysium has aspects of his mind shouting their input at him. Grobian, like a devil on your shoulder, proposes “renegade” options. Beatrice is virtuous and kind. Socrates is balanced and measured. Players can listen to these inner voices before making decisions of their own. This system is interesting, and Grobian in particular provides some refreshingly silly and crude ideas, but it feels a little underused, like a few too many of Pentiment’s more oddball or supernatural tangents.

Pentiment features music by Alkemie, a group specializing in authentic-sounding medieval and folk music. When it’s there, the music is dripping with atmosphere, but I did feel that background music was sparse and underutilized until the final act. At times, this quiet made the game feel overly sleepy, to the point where I thought my game had frozen mid-conversation more than once.

As far as dialogue goes, Pentiment makes the aesthetic choice to have each character write or type out their lines in floating scroll-like speech bubbles, with absolutely zero voice acting. Instead, the script type and fonts characters use showcase their personalities. The peasants of Tassing have their words scrawled out, while the monks and nuns of the abbey “speak” in fine, gothic penmanship. Some more forward-thinking characters even have their words printed out, as in spelled out and stamped in block print. Interestingly, the chosen fonts sometimes change with Andreas’ evolving perception. A peasant who reveals they are literate or mildly educated suddenly speaks in finer handwriting. Admittedly, the constant scribbling noises and sometimes inscrutable text can be frustrating, but Pentiment offers the accessibility options to change to more legible fonts.

Accessibility, though, is otherwise not one of Pentiment’s strengths. For one, there is no dialogue history to scroll back through, nor is there a way to even see the most recent previous dialogue that you are expected to respond to. Perhaps this is a conscious design choice to make players pay close attention (after all, dialogue is the only real gameplay element here), but it seems like an oversight to not even make it a selectable option. Similarly, the menus are clunky and limited (such as having no inventory for key items), and the journal entries Andreas logs to keep track of learned clues and objectives are nearly useless, either cumbersome or shockingly vague. This means that I was forced to juggle names, clues, items, and leads in my head. Again, perhaps this was by design. Personally, I liked how the game subtly pushed me to constantly think, but I can also see this as a point of frustration, especially for players who take long breaks between play sessions. If any important decisions come up, it’s best to play until you see them through.

Speaking of important decisions, the sheer number of my choices the game retained is staggering. Though you rarely get the in-game message “This will be remembered” after key moments, in truth the game takes everything you say (or don’t say) into consideration and calculates all of it in pivotal scenes. Were you too quick to criticize the church? Were you even momentarily gruff with an elder monk? Did you show interest in the daily plight of a peasant farmer? Once I was aware of this, everything I did carried weight—and with the game’s continual auto-saving, there are no takebacks and no save-scumming. Andreas must learn to live with his actions, which become matters of life or death once the game’s central plot of solving a series of murders over twenty-five years at the Abbey comes into effect.

As Andreas, you must uncover the many secrets housed by the villagers and monks of Tassing and Kiersau, pursuing too many webs of clues with too little time. It’s intentionally impossible to see everything before each act’s deadline. Without spoiling how things turned out for me, heads in your playthrough will inevitably roll, and Andreas must choose whose. Andreas—and the player—can’t have complete insight into whether his assumptions were correct, which lends itself to the theme of faith that is so prevalent: “Blessed are those who believe but have not seen.” Your Andreas may be a saint or a heretic, but there is no clear right or wrong at the end of the day. You must choose to believe that you made the right calls (and got the right people killed) if such a thing is possible to begin with.

I must also address something that is sure to bother some fans of Obsidian’s usual work: there are no alternate endings. There is a definite (and satisfying) ending to the overarching mystery, but all players end up with the same single ending (with minor variations on the epilogue). I wonder if this isn’t director/writer Josh Sawyer’s nod towards religious predeterminism, or the inevitability of death. Some are bound to feel like their choices have no weight, ultimately. The role-playing elements of Pentiment, though, can draw players in and show them the importance of their choices in everything leading up to the finale. In many ways, Pentiment requires players to have faith in the stories they’ve spun for themselves.

While many players are bound to find gripes in agreement with some of my earlier points, let me be clear when I say that Pentiment’s writing, characterization, and thematic depth shine so brilliantly that they block out its flaws. It’s so, so intelligent. The many characters of Tassing feel like living, thinking beings, complete with complex motivations, staunch political and artistic opinions, and utterly human reactions to the consequences of Andreas’ sleuthing. As you jump years ahead between each act, you’ll find yourself rushing to the Gertners’ farm to see if little Ursula got over her seemingly fatal cough, or to the nunnery to see if a certain monk and nun have run off and eloped, or to the blacksmith to see if he ever found love, or to see if the strict taxes imposed by the abbey were too much for the peasants to survive. There were many characters I loved, some I hated, but few I felt ambivalent toward.

Obsidian’s medieval murder mystery Pentiment is a small but incredibly dense narrative with little gameplay but heaps of some of the most exquisitely crafted dialogue in all of gaming. It’s more captivating than it is exciting, and it may appeal more to readers rather than gamers. I thoroughly enjoyed my time with it and already know its writing will stick with me far longer than most bigger, more technically impressive games.